There’s a certain fascination with gold; it seems to offer a way to constrain central bankers, at one end of the rules versus discretion debate. Mind you, central banks don’t have a stellar track record. The Federal Reserve raised interest rates during the onset of the Great Depression, surely worsening matters. That’s a core criticism of Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz in their Monetary History of the United States. So it’s sensible to ask if there’s a viable alternative.

Drawing upon Irving Fisher, Milton Friedman played around with rules that focused on the growth of the monetary base. Empirically, the first pass seemed to be OK. However, that turned out to be an artifact of his particular dataset, drawn from the early post-WWII period in which financial institutions in the US were tightly regulated. By 1980-81, when the Fed briefly tried to use such a rule under Paul Volcker’s chairmanship, it was clear that there was no stability of the link between creating additional reserves and banks’ creation of money. So if not reserves, then let’s try targeting monetary aggregates, first M1 then M2. When those proved unreliable, then let’s try an inflation target, now part of the legal mandate for the Bank of England. That, too, has problems; the latest iteration is to focus on holding the constant the growth of nominal gross domestic product. As to Friedman, he eventually concluded that none of the rules he proposed would work. But that was in his academic publications, and in talks before economists. He never went back to emend his popular writings that propounded what has been labeled “monetarism.” Nor did he support the gold standard; to reiterate, in his analysis it was the US attempt to adhere to the gold standard that turned a recession into the precipitous decline of the Great Depression.

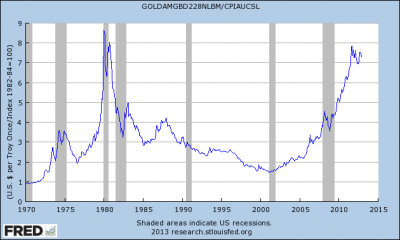

So what’s wrong with gold? For one thing, any claim that it provides a stable source of value fails to pass the laugh test. Jewelry fashions come and go; central banks buy gold and then don’t; mines dry up; the global economy booms. All affect the price of gold. Over the past 4 decades (setting 1970 = 100) the price rose to 950 circa 1980, then fell to 150 by the 1990s, and has risen again to 750. Traders in shopping malls booths wouldn’t have a business scamming people out of their grandparents jewelry and selling overpriced coins if the price of gold was stable. One of the largest sources of gold is Russia; do we want to give Vladimir Putin the ability to thrust us into a recession if somehow Congress were able to forge a direct link between gold and the US macroeconomy? I suspect not.

Now it’s unclear why Rand Paul latched onto gold; I suspect it was that he really wasn’t “into” economic policy and never did his homework. Then, too, there is the residual impact of the writings Hayek and other “Austrians” that go back to the days when it looked like monetary policy rules might work. That is compounded by the Austrian school’s loss of focus once high socialism was no longer a real threat. Hayek and others engaged in broad-brush arguments against socialism, with the Soviet system as their implicit target. It’s hard for young people to fathom, but at one time that model seemed a real threat, both with the Red Army’s continued occupation of eastern Europe, and the attraction of Stalin and the meteoric rise of of Russia from a backward peasant society to a military and scientific power that could provide many of the appurtenances of middle class life to its core population. In contrast, England’s economy didn’t do very well after 1914, and did horribly after 1929. In newly independent colonies, the political model also seemed attractive; bedeviled by unnatural geographies and ethnic tensions, democracy didn’t look workable in the short run, and presidents who developed a fondness for the trappings of office found Stalin’s example of how to hold onto power more useful than trying to learn lessons from Churchill’s electoral failures. But in 1989, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and within a few years of Tiananmen, the success of market-oriented reforms in China. No one now views socialism as a threat.

Unfortunately, the Austrian school has nothing to say to this new world; its raison d’être vanished in 1989. Yes, government is bad. But we’re no longer talking about the heavy hand of the central planners in Moscow and their cruder counterparts in Romania or Beijing. The Austrian’s broad-brushed treatment is not amenable to empirical exploration; ironically, unlike the teachings of Marx, it is more political philosophy than economics. (Marx’s theories, of course, have been found wanting.) So the Austrians have nothing to offer policymakers, they have no ability to provide a nuanced picture of an economy. Another irony is that without the foil of the Soviet Union, those enthralled by the writings of von Mises and Hayek have become doctrinaire, arguing over fine points, hostile to any who are not true believers. I had hoped that mindset died out with the last generation of Marxists, only to find that today it characterizes the Right rather than the Left [both capitalized – after all, they are/were proud of the label].

Now Ron Paul is an engaging speaker; I’ve heard him. He makes enough sense here and there to encourage people to listen. But he ranges too far and wide. When it comes to economics, he may have a store of one-liners, but they don’t add up to a coherent story.

6 Comments

I would like to argue a few points in the order they are laid out in the article:

1. “So what’s wrong with gold? For one thing, any claim that it provides a stable source of value fails to pass the laugh test.”

When you compare the price of gold to US dollars and see price movements by a factor of 16 over the last 40+ years (BTW starting the chart one year prior to the US completely abandoned the gold standard of the currency obviously adds to the volatility) it might be worth it to investigate whether it is the price of gold or the USD that is fluctuating so wildly. Go to http://pricedingold.com/ to see if gold or the USD has had more stability of value over time.

2. “No one now views socialism as a threat.”

I would argue that a significant portion of the US population that pays attention to such things views the current US government as a socialistic threat. However, most of those who see socialism brewing in the US look to the Republican Party to lead them away from it and so far they have not been doing a very good job.

3. “Unfortunately, the Austrian school has nothing to say to this new world; its raison d’être vanished in 1989.” …. “So the Austrians have nothing to offer policymakers, they have no ability to provide a nuanced picture of an economy.”

This couldn’t be further from the truth! In less than an hour on YouTube one could watch numerous speeches by Ron Paul (as well as other Austrians) who predicted the dotcom bubble, the housing bubble and the 2008-2009 crisis. When being interviewed about how he saw these things developing while most of the country was basking in “irrational exuberance”, he credits Austrian economic theories of the business cycle and the dangers of government interference. He reveals to us the coming problems and offers policymakers solutions.

1. The US has had neither hyperinflation nor hyperdeflation — what we can buy with a dollar has not changed very much during this time period. It’s the price of gold that is volatile.

2. I have absolutely no idea what “socialism” means as you use it. If it’s the government role, Obama is more conservative economically than Bush — for example, he pushed GM and Chrysler into bankruptcy rather than giving them handouts. The government role in the economy was greater under Eisenhower — if Obama is socialist, then are you accusoing him of being a Communist?

3. The Austrians are always predicting crises. Once in a while one occurs, but that doesn’t lend credence to these claims, it means only that if you say enough different things, some of the things you say will come to pass. The economist’s test: if these claims are any good, then the Austrians ought to be the richest people on the planet, because you can turn accurate predictions of gloom into … dare I say gold? To see who the people were who actually got it right, and had the confidence to bet on it, read Michael Lewis’ The Big Short. These folks weren’t Austrians — nor were they “efficient market” types.

I disagree fundamentally, philosophically – not to mention my BS meter is flashing red and squealing loudly!

1. I’m not sure how this could be taken seriously. I’m sure you have a chart that shows relative pricing power of the USD is fairly flat over some period. Anyone alive over the past few decades “knows” that such a chart would be depicting some central planners fantasy land of how great of a job the planners have done.

It may even accurately depict how flat the prices have been for the “elite”, i.e. those closest to the spigot of the Fed’s and the banks’ dollar generating schemes. But it is a far cry from the reality of 99.9% of those who use those dollars down the line, when the price inflation has already fully taken hold. We all have lost purchasing power, but I’m sure the charts show otherwise.

On a philosophical level (which is what Austrian economics is more than anything) how could a rare element of this earth have a more volatile price than man made, manipulated (with an unlimited supply) for political purposes, pieces of paper with numbers printed on them? When you compare how much a gram of gold is worth in apples, oranges, fine clothing, furniture, prime property, houses what will you find?

How about this: If you wanted to pass on some wealth to your great grandchildren would you give them an ounce of gold or seventeen $100 bills?

2. I’m definitely not attempting to make any distinctions between Bush and Obama since there are very few.

It is plainly false to say Obama didn’t give GM handouts. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Motors_Chapter_11_reorganization

I suppose “cash for clunkers” was a government intervention aimed to help “the people”, not GM?

The US Treasury gave them secured loans for hundreds of millions of dollars.

They also dissolved and magically reappeared as a “new” GM. They did not go into traditional bankruptcy. You can buy shares of the “original GM” for 4¢/share (MTLQQ)

3. The Austrians believe government intervention and central planning is always worse than free markets. To say they are “always predicting crises” to mean they flail around talking about the sky falling and the end of the world is a handy way to gloss over the fact that they have accurately predicted the (1)dotcom bubble and the fact that the (2)housing bubble would lead to the (3)economic crash – starting in 2007/8 – which has yet to fully transpire due to the government intervention of endless rounds of QE.

Austrians find QE as the cause of the next bubble. Keynesians find QE as the solution to the last one.

It is a common tactic of the Keynesians like those on CNBC, et al, to tell someone like Peter Schiff (they have been ridiculing him on air for more than ten years) that he is not to be taken seriously because he has been calling the collapse of the dollar and it hasn’t happened yet. That’s the kind of (lack of) critical thinking that has us in our current precarious situation.

I don’t know if Peter Schiff or Ron Paul profited from these situations but they sure nailed the problem and the cause. Dozens of videos on Youtube.

Ron Paul has had to publicly verify (due to his post as Congressman) that he has been buying gold and stock of gold miners for decades … he’s doing well on that prediction/investment.

I haven’t read “The Big Short” yet. However, in Michael Lewis’ book “Boomerang” he features Austrian Kyle Bass who “got it right” and made billions on the housing crash.

The US data on consumer prices reflects very carefully designed methodologies that are used by independent groups in countries such as Argentina and Brazil where the government did try to skew reported inflation numbers. (Such independent research also exists for the US.) You can get several hundred separate time series from the BLS and construct your own favorite; BLS tries to reflect the US average consumer and the wealthy don’t outweigh the bottom 50%, they are but 1%…or less. We know what retirees consume, and what poorer households consume, and can calculate indexes specific to them.

Whether the price of a commodity is more or less volatile than inflation is an empirical question. In the case of gold, the answer is that the price is not stable and is not a good store of value. In fact, the price of gold (corrected for inflation) remains below that of the one time I bought gold (for a wedding band, and also a nugget from a friend in need to whom I paid the full market price, rounded up at that). When I add in foregone interest, which has consistently been above inflation (positive in real terms) I would be better off today if I had left my money in the bank. [Plus my wife promptly lost her ring, removing gloves at the hospital where she worked…it costs money to store gold safely.] Given this, I bought savings bonds for my children, much better for them than if I had bought gold. Now because gold is volatile in price (a function of short-run supply and demand price elasticities and income elasticities) you can always find time periods when it does better. You can find periods when it does worse. On average it is not a good store of value.

For my students: does buying fools gold — iron ore — perform better than buying gold? I have no prior; my hunch is because of significant demand for productive purposes it has kept its value relative to inflation, but as with gold it is subject to shifts in mining technology and demand for business cycle and other reasons.

I don’t watch talking heads of any stripe, so while I recognize “CNBC” I have no idea who the people are. When I see someone bandying about the term “Keynesian” however I know that they have little or no knowledge of economics; Milton Friedman after all used the analytic framework of Keynes as the core of his analytic work. Keynes resigned in protest to the policy disaster of the Treaty of Versailles, he had no illusions about government being superior. His “General Theory” was motivated by fears of the left, he abhored socialism and was worried that the Great Depression would lead to a collapse of the British society and the freedoms it provided.

Similarly, when I hear people predicting the future in vague terms (“dollar crash” “the sky is falling”) I stop listening. Michael Lewis wrote about participants (investment bankers) who focused on specific places where financial markets were inefficient and focused on specific prices and time frames. But his work suffers from the survivor’s balance; there surely were others who bet too early and so lost everything, or who weren’t close enough to the market to focus on the one specific instrument that enabled large bets. That particular market was thin, too, and they basically bought the entire market. In contrast “dollar crash” is useless, nay, dangerous, as investment advice.

I acknowledge this conversation has run its course, so if you wish to reply again I will leave that as the last word. I appreciate your thoughts.

The most obvious disconnect here (obviously, other than what appears to be opposing philosophical differences) is my lack of knowledge in the study of the history of economics and the semantics involved in “proper” academic discourse, which has now finally led to it’s predictable (I have had such discussions before and appreciate your toleration) dismissal of ideas presented which are not grounded in that structure. While I respect your expertise in economics I am also reminded of the fact that dismissing ideas that derive from laymen, using laymen’s language and, most importantly, then twisting those ideas – which spring out not from the crusted over theories and long held beliefs of the “experts” and academics – to be coming from “someone who has little to no knowledge of economics” and therefore “stop listening”, is a dangerous proposition. No matter the subject.

Time is short and I understand it’s impossible to quid pro quo every point in a discussion such as this. I plead any reader to find those points which were either ignored, dismissed or glossed over by the prof and dig a little deeper. These are often the points where the advocates of central planning (what we neophytes would call, with a broad brush, Keynesianism!) have weak/no answers against an Austrian argument.

To cast any of what I have said as “investment advice” once again changes the scope and entire landscape of the original discussion, which was mainly about the folly of Austrian economics. As such, I would be grateful to get your expert opinion on the following issues as they relate either to your ideas or what you perceive the ideas of the powers that be might implement.

How do you see the current situation of the US Treasury ($16 trillion in debt on the books, up to $100 trillion in unfunded liabilities over the next generation, deficit spending around $1 trillion per year for the foreseeable future with the tax situation as it is or could be in the future) resolving itself, especially in the long term (5-50 years)?

What is the likelihood the current situation will end in default of the debt or hyperinflation (monetizing the debt)?

What are the chances the USD, in its current form, will be a useful currency in three generations (which was the basis of my great grandchild question last post – it was not taken to be an investment question)?

Is it wise to have very few (13?, 50?, 100?) people determining, to a great extent, monetary policy for the 7 billion people on this planet?

Thank you for allowing me onto your cyber space to have this discussion. Good luck to you and your students on your endeavors.

Three generations is a long time; in 75 years China’s population will be in sharp decline, Japan much smaller and so on. India will likely be the largest society in population, perhaps in its economy. Will the US$ remain the dominant currency? Perhaps, because it is hard to tell a story of the currency of another country being so strong as to displace it, mainly because it’s hard to see any single country becoming more than “first among equals”. Will the US economy still use dollars? Of course! Will the rest of the world? I suspect so, but I’m not sure it matters.

The current US fiscal situation is in large part due to the current recession (and a couple unfunded wars, and a large extension of medicare [Bush’s prescription drug plan], all accompanied by revenue cuts). Because we rely on income taxes, revenue is much more volatile than the economy itself. In addition, the shift to greater income inequality means that more wealth & income are sheltered, Mitt Romney paid an effective rate lower than that of someone on minimum wage. Ditto the corporate side: when GE pays no taxes year on end, well, that suggests a problem. Now that may be icing on the cake, but if the cake is pretty unpalatable….perceived inequity makes holding a calm discussion harder. So economic recovery will help the budget enough to last a long while.

Social security is very close to being in balance; the real fiscal issue is healthcare, and while costs have risen less rapidly in recent years, it’s still the fastest growing component of the consumer price index. If cost increases can be contained, then most of our short-term fiscal issues disappear. As long as we continue our grqdual recovery from the Great Recession, we can wait a decade before addressing them. I’d rather see us start sooner, because it’s easier to adjust with [gross] debt of 80% of GDP than 160% of GDP, but there’s no crisis in the sense of something we have to do immediately. Oh, and if you go through the arithmetic, high inflation doesn’t get around the problem, because the key obligations are indexed directly or indirectly. You can get a one-time gain in revenue from inflation, but ongoing gains require geometrically accelerating inflation. The only recent case of that is Zimbabwe (and maybe the Ukraine?). However dysfunctional our political system might seem, our disputes are nothing in comparison to Zimbabwe’s. To get to hyperinflation requires a society that is melting down already.

If you build a macro model — interactions — rather than a micro model — a single market — then it’s difficult to tell a “melt-down” story for the US dollar that is internally consistent. The big currency collapses (Argentina, for example) are consequent to trying to fix a currency, to make an economy in flux rotate around a single price, particularly when the initial price is too strong so that a country runs trade deficits and runs out of dollars (Argentina again). Or they stem from borrowing in a currency not your own (Thailand in 1997), which is fine if a currency is truly bound to another, but disaster if it becomes unpegged. But we aren’t that closely tied to the rest of the world (trade is a small share of US GDP) and while non-residents hold lots of debt, it’s all denominated in dollars. For the individual investor that may be fine, but China has a generation’s worth of savings tied to our financial markets. We’re interdependent, but they are more vulnerable in both economic terms and in domestic political fallout.

This is not the position of a Pollyanna. Growth of 1% pa rather than 2.5% over 3 generations is the difference between GDP doubling and GDP increasing 6-fold. Waiting a decade to start addressing fiscal issues (any implementation ought to be gradual) pushes us toward the former. Compared to the rest of the world we are undertaxed and underprovisioned with public services and infrastructure. Of course throwing money at education doesn’t guarantee we’ll do better. Refusing to educate (California has largely gutted its community colleges, once a tremendous avenue of social mobility) in the name of saving money is penny-wise and pound-foolish: it guarantees we do worse. The particulars of our federal structure create challenges for addressing national issues such as education that rest upon local (or state) implementation. Not all our problems are macroeconomic, but bad macroeconomics makes the micro harder to do.

Finally, is putting monetary policy into the hands of a few dozen people on a global basis make sense? No. However, we know that putting it in the hands of a really large group of people (like multiple legislatures) is a really bad idea. Small committees tend to move slowly, when the members are all selected from a group of successful and smart individuals it’s hard for single indivudal to dominate. The main danger I see is falling into group-think. Even worse than a large group (inevitably of politicians) is a dictator: we know that placing power in the hands of one person increases the chance of error dramatically. (Put it another way: that’s mandating group-think.) Finally, turning to iron-clad rules puts monetary policy in the hands of a dead politician, worse than even a live politician, because at least a live politician might have to face the consequences of bad decisions. Economies continue to change (the word “evolve” is too tied to teleogical imagery, “progress”, but in strict biological use means continues to adapt to the environment). So while clearly imperfect, relying upon a small group of bright and ambitious economists may be about as good as we can get.

But perforce our understanding is backward-looking, we fight yesteryear’s wars. So we’ll see policy mistakes, but central bankers tend to be pretty conservative in several senses of the word, and at least a smattering of them have sufficient intellectual integrity to react when things don’t work as expected. Greenspan was a radical, an eternal optimist, and not very tied to theory; luck was with him for a long while, but he was not the best person to be watching for dark patches in gray clouds. Bernanke is conservative, with a deep historical knowledge, and he is aware of how badly things can go wrong, which engenders a degree of humility. But in any case we’re in an environment where he has few tools at his disposal, short-term interest rates can’t be pushed below zero, though he still tries a few new tricks in case some of the economy’s parameters turn out to be not quite one [= nothing happens].

A last response, lest my employer try to charge you tuition (and chide me for providing courses for free). But hopefully food for thought.

Comments are closed.