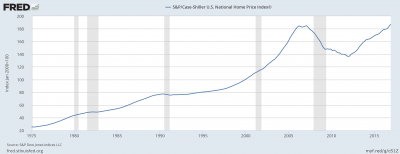

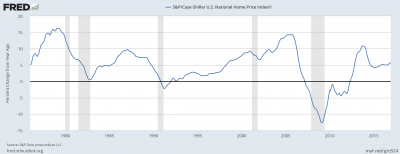

The long-term visualization of home prices in the U.S. tells an interesting tale of overall domestic growth, labor force demographics, and mortgage industry changes.

Beginning in 1975, housing prices rise fairly steadily. A number of industry reforms aimed at providing credit to underprivileged demographics may have aided this growth (most taking place in the 70s.). However, labor force demographics are likely the main drivers, as baby boomers entering the labor force created higher demand for housing following 1980s economic expansion.

Home price growth was relatively flat throughout the early 90s, but seemed to increase exponentially from 1995-2006. Early home price growth in this period may be attributed to baby boomers moving from urban to suburban residential communities as they started families. Homeowner demographics also changed as easier access to credit allowed for lower income individuals to be accepted for a mortgage. The securitization of mortgages allowed mortgage-lending institutions to supply the loan and sell the debt, removing the risk associated with lending to less qualified mortgage applicants.

With more “qualified” mortgage applicants, demand soared until 2008. Once home prices had plateaued, lower income individuals could not refinance their homes using higher market values. As a result, many defaulted on loans and walked away from their debt obligations. Housing supply was in a large glut, leading to a collapse in home prices (and in the prices of mortgage-backed securities), and the ensuing recession.

7 Comments

It is interesting to note that a lot of the change in home prices (increases) before 2008 seems mainly driven by the actions of baby boomers. On another blog post, the question was raised over whether we would need another baby boomer generation in order to generate economic growth. However, as discussed in class today, it seems unlikely that people will keep continuing to have as much kids as before – partly due to the costs outweighing a lot of the benefits – and I wonder what the impact of this could be on home prices, especially if people are opting to not have children and stay in apartments versus houses. I don’t know how big of an impact this will have, but in theory, if families consist of fewer individuals then I wonder if demand will fall for housing as opposed to alternatives. However, I’m not sure if the theory would hold in real life, so it would be interesting to see if there is any relationship between births and home prices.

I thought it was interesting that some of the increase in home prices can be attributed to suburbanization from Baby Boomers. I wonder if the reverse will happen with our generation with a housing boom attributed to urbanization. Most of us plan to move to a city after graduation, and this creates more competition for apartments and houses that was previously seen during the Baby Boomer flight from cities. Although I don’t know the long-run trends of Millennial home-owners, seeing home construction trends across the country would be an interesting graph to compare with this to see a full picture of new housing trends.

So over the long run (that is, relative to the S&P) house prices look like any other asset class? We may have a lot of “noise” (up and down cycles) but part of the decision then is based on expectations of the “return” on owning a house. Now the calculation is not quite so straightforward, as a mortgage doesn’t include taxes and insurance and so on, while interest is deductible from income tax. Still, there is the correlation in the graph above.

Playing off what has been said above, I, too, am interested to see whether or not housing prices will move in the opposite direction for our generation than for Baby Boomers. As many earlier posts have stated, our generation has been characterized by urban migration. Increased demand for multi-purpose neighborhoods and public transit have limited urban sprawl, and pushed populations back towards city centers. Will we see a significant drop in housing prices in suburban areas?

I’ve also wondered how the psychology of home-owners could change the overall market demand. Although Millennials may be moving to urban areas now, I think it is more likely that suburbanization would occur than a mass urban development sprawl. However, how fresh is the recession in peoples’ minds? Sure, regulations may be in place to prevent the same housing market bubble from occurring, but will housing demand remember getting burned by the time our generation decides do move away from downtown areas? If we consider housing as an asset class (as mentioned above), how short is the market’s memory?

An interesting point was made above. It is clear that the birth rate in the US is declining, and immigrants typically have lower income, making them more likely to opt for an apartment over a house. To refer to the previous blog post, would this not apply downward pressure on housing in the large urban centers like New York and Los Angeles? This begs the question of how much longer we can expect to see a long run trend of increasing home prices. Would the wave effect in birth-rates have a similar effect on housing prices? Low birth rates causing low demand and therefore low prices, followed by a rebound in births, and an associated rebound in prices? Could such a phenomenon be detectable?

A couple issues. Well, more than two, I’m sloppy with my prose.

How much excess housing was created during the 2003-2006 real estate bubble? Where? It wasn’t uniform across the US.

The population is growing and housing depreciates. So at some point any excess housing will be soaked up – vacant houses get torn down. The extreme are chronic high humidity locations in the South: if air conditioning gets turned off, carpet and walls start rotting very quickly, in less than a year a house can be so full of mold that it can’t be fixed, the only option is to tear it down.

New household formation affects the demand for single-family dwellings. Marriages fell during the Great Recession. That is part of the supposed “new generation” behavior. As an economist I’m skeptical about claims of sudden changes in culture, that Millennial thing. Rather I hypothesize it’s an endogenous response to external conditions, which includes tighter credit standards for getting a mortgage.

The aging of the population also shifts housing demand, more older individuals in small households (including single-person households) plus downsizing. Will there be enough younger households wanting to transition to larger homes to keep prices from falling? A capstone some years back looked at simulations and concluded that the effect would be small.

What happens at the local level can be very different from the average for the US as a whole. Ours is a big country!

Comments are closed.